As we arrived outside the

Banksy crossed from subculture to mainstream a few years back, following his move from Bristol to the art capitals of the world, a bestselling coffee-table art book, and his work getting regular exposure on TV and in the international press. Not to mention the phenomenally high prices being paid for his paintings at auction. So this is the local boy giving something back to the hometown that still bears the marks of his early stencil-work. The flyer says “PG Contains scenes of a childish nature some adults may find disappointing”.

The queue turned out to be for one and a half hours. I usually avoid events you have to queue for, but it was a nice sunny day and we were treated to the occasional sight of middle aged women joggers dressed in pink bras puffing and panting their way up the hill in support of a breast cancer charity. Also I found the queue added to the theatre of the occasion, and as you got closer to the entrance of the museum, the excitement seemed to build with the first whiffs of aerosol paint.

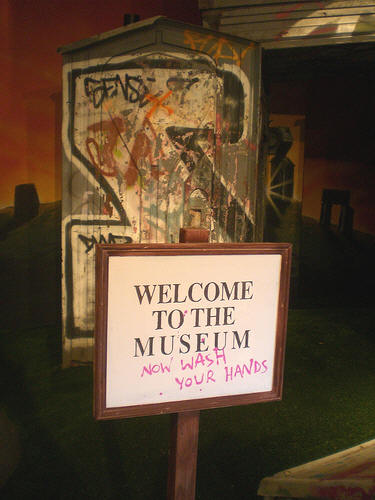

And it also added to the irony of the occasion, as you’re shepherded into a really old-fashioned museum by security guards employed by an artist who has built his reputation on dodging security guards. And this is to see art that has an image that is supposed to be way too rebellious to be sanctioned by fusty old institutions such as this.

And it also added to the irony of the occasion, as you’re shepherded into a really old-fashioned museum by security guards employed by an artist who has built his reputation on dodging security guards. And this is to see art that has an image that is supposed to be way too rebellious to be sanctioned by fusty old institutions such as this.

The artist has chosen to hire this museum and cover all the expenses for what must be his first major show in this country. And admission is free. And there’s no Banksy merchandising at the museum, apart from the book “Wall and Piece” (which you find all over Bristol anyway) though the Oxfam shop across the road is doing a nice line in Banksy stickers and postcards.

So, we found ourselves being corralled into this old stuffy museum and being greeted by friendly museum  staff and - thank goodness - they don’t have art explainers showing you round.

staff and - thank goodness - they don’t have art explainers showing you round.

At the entrance, there’s a

As you shuffle down the corridor, there’s a candlelit shrine in homage to the recently deceased pop star, Michael Jackson (below). It’s an oil painting in Victorian genre style of a fairytale cottage in dark woods, with The King of Pop as the wicked witch Jacko leaning out of the doorway offering candy sticks to tempt two lost children inside.

Once you’ve got through all this entrance malarkey, you’re free to wander round the displays, and the museum is large and not so crowded once you get inside. And you’re allowed to take photographs.

The first room is exclusively Art of Banksy, with a militant looking false ceiling of army-surplus camouflage net. And behind a screen of chicken wire you can see a full-scale mock-up of the artist’s studio, hung with loads of cardboard stencils, newspaper headlines about Banksy’s graffiti, filing cabinets are labelled “good ideas” “bad ideas” “other people’s ideas” and “porn”, a knitted cardigan that reads THUG FOR LIFE hangs off the artist’s chair. There’s the sound of a London radio phone-in on some Banksy controversy or other. On the easel is an oil painting of pixellated-faced portrait of a hoody in a baseball cap, the same self-portrait used in the Wall and Piece book.

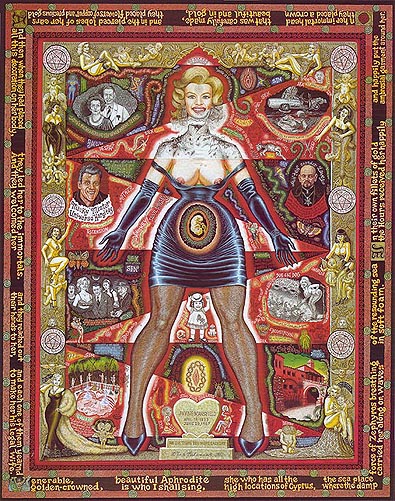

The walls of the rest of this gallery are covered in “original” Banksys (as far as “original” work is concerned, just about every image in the show is a remix or update of existing cultural product), paintings on canvas, modified reproductions of paintings, small drawings.

The walls of the rest of this gallery are covered in “original” Banksys (as far as “original” work is concerned, just about every image in the show is a remix or update of existing cultural product), paintings on canvas, modified reproductions of paintings, small drawings.

In this gallery setting, it is possible to admire the quality of the brushstrokes and to examine closely the various techniques used to remix and remodel. On a craft side, it’s obvious that the guy works with a range from hands-on traditional craft skills to computerised techniques. He can draw, he’s pretty good at painting and can cut a mean stencil. And he’ll tend to abandon technical virtuosity or anything “deep” in favour of quick visual impact.

Rather than calling it the culturally-loaded term “art”, Banksy-work may be more precisely described as expanded media-cartooning which plays with the signifiers of modern urban experience. Each piece within the show works as an easily-readable visual joke. The humour is often cheesy and has gently satirical edge, the context and framing of the work is vital to its meaning. A lot of the jokes are mild, usually visual puns or updates of familiar old paintings. Both the strength and weakness of his output lies in the fact that rather than serious message, serious technique, or serious “cool”, Banksy tends to err on the side of cheeky humour.

In the next room are the pieces that I’ve really come to see, the animatronic petshop. There are surveillance cameras acting like roosting birds, fish fingers swimming round a goldfish bowl and lots of little cages with pet sausages wiggling about in them.

In the next room are the pieces that I’ve really come to see, the animatronic petshop. There are surveillance cameras acting like roosting birds, fish fingers swimming round a goldfish bowl and lots of little cages with pet sausages wiggling about in them.

The animatronic effects are of

Throughout the rest of the museum, there a mixture of the museum’s collection and additions by Banksy. There’s a burned out icecream van converted into an information booth, modified faux marble statues and joke oil paintings inserted into the museum’s existing collection of old masters. You find yourself on a treasure hunt of Banksy interventions, and sometimes you’re not quite sure what if you’re looking at is part of the museum’s regular display, or a Banksy addition. An ornate gypsy caravan has been issued with an eviction notice. A stuffed fox in a British wildlife display holds a bloodied Countryside Alliance placard.  There’s a hash pipe inserted into another display. I’m not sure whether the “Dinosaur Sick” is an original part of the fossil display or a Banksy addition. In the modern art room, a Banksy-looking painting of a bombed-out farmhouse turns out to be the once-censored “A Farm near St Athans” (1940) by official war artist John Armstrong.

There’s a hash pipe inserted into another display. I’m not sure whether the “Dinosaur Sick” is an original part of the fossil display or a Banksy addition. In the modern art room, a Banksy-looking painting of a bombed-out farmhouse turns out to be the once-censored “A Farm near St Athans” (1940) by official war artist John Armstrong.

A common technique in Banksy’s art is to play on the edges of the surface on which he is painting. Figures wander out of holes to take a break, a waterfall spills out of the bottom of a painting, UFO's fly out of the canvases zapping ancient galleons with death rays. The grit and mess of the urban environment is integrated into the stencilled paintings, giving texture and trompe de l’oeil visual puns: painted figures engaged in the act of painting.

Everything in this show is humorous, and it’s just as often daft, trite and sloppily done as it is carefully executed. The work is both about messing with illusions and creating the illusion of Banksy as pixellated superhero dodging the surveillance cameras, breaking free from Disney-matrix mind control and sticking two fingers up at Burger King. The meaning of these images is created by the way they are set up in this particularly stuffy kind of museum: the kind of museum you get dragged round on school visits, and not all  cool and white-walled and trendily-converted former industrial-space like the Tate, Arnolfini, Exchange, etc etc.

cool and white-walled and trendily-converted former industrial-space like the Tate, Arnolfini, Exchange, etc etc.

I really enjoyed the show, it was far better than I expected. The dodgy quality of a lot of the work humanised it and made it seem more intimate and uncontrived. As well as there being more jokes, there is an ethical dimension to Banksy’s work which makes a refreshing change from a lot of contemporary art-bollocks.

Looking at criticism of Banksy, I think a rather false argument arises about whether his art is “subversive”. Certainly Banksy consistently plays with the idea of subversion, in the imagery used, in the means of production, and in his pseudo-anonymity. Throughout his work there is a constant ridicule of authority figures and institutions, including contemporary art institutions. This is in common with a lot of youth- or subculture-oriented cultural product. It has a broadly leftist/anarchist/punk/environmentalist undercurrent and consistently celebrates “street” culture. Twenty or thirty years ago this kind of art might have been seen as more subversive than it does these days. Back then, along with the CND, Trades Unionists and new age travellers, artists like this might have attracted the attention of the security services, and even found themselves on Maggie Thatcher’s hit list. Nowadays a few minutes on Google will tell the shape-shifting lizards in charge of the secret state all they need to know about this artist’s real name, what he looks like, where he went to school, who his Facebook friends are, etc.

If being subversive means it undermines the way we currently relate to art, globalised capitalism, and the mythology of artist-genius, then of course Banksy’s work isn’t subversive at all. The way the world is at the moment, to work as an autonomous artist and to live out the myth of individualism by “expressing yourself” requires an amount of financial cushioning, whatever scale you work on. Banksy is best-known for his unsanctioned painterly interventions into the civic landscape. Remaining anonymous may be sensible to remain ahead of the legal repercussions associated with this kind of activity, but this is a pseudo-anonymity, as the signature BANKSY has often featured heavily. The artist with the Banksy tag has been using the celebrity-commodity system in a very pure form, creating the specific artist name, artworks related to this name and the idea of one person as a genius behind it. Speculation about the “real person” behind the name creates a media story which Banksy continues to exploit. So the artwork follows the specific rules of capitalist production, aimed to accumulate economic capital and/or symbolic capital which is the currency of all scenes and subcultures.

If being subversive means it undermines the way we currently relate to art, globalised capitalism, and the mythology of artist-genius, then of course Banksy’s work isn’t subversive at all. The way the world is at the moment, to work as an autonomous artist and to live out the myth of individualism by “expressing yourself” requires an amount of financial cushioning, whatever scale you work on. Banksy is best-known for his unsanctioned painterly interventions into the civic landscape. Remaining anonymous may be sensible to remain ahead of the legal repercussions associated with this kind of activity, but this is a pseudo-anonymity, as the signature BANKSY has often featured heavily. The artist with the Banksy tag has been using the celebrity-commodity system in a very pure form, creating the specific artist name, artworks related to this name and the idea of one person as a genius behind it. Speculation about the “real person” behind the name creates a media story which Banksy continues to exploit. So the artwork follows the specific rules of capitalist production, aimed to accumulate economic capital and/or symbolic capital which is the currency of all scenes and subcultures.

Nigel Ayers 25//7/09

Photos by Lesley Ayers

(for www.artcornwall.org)

There are flaws in the concept of an 'art world', it is a fact of postmodern life that there exist many parallel, overlapping and contra-orbital art worlds.

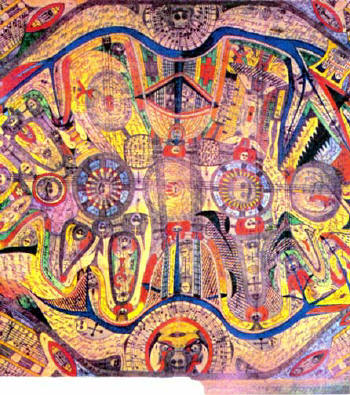

There are flaws in the concept of an 'art world', it is a fact of postmodern life that there exist many parallel, overlapping and contra-orbital art worlds.  In some cases it can be argued that the creator acted without any artistic intention, creating as part of a private personal belief system, rather than social reasons. For example, during his lifetime Henry Darger worked as a lavatory cleaner in Chicago hospital. He was never known as someone who wanted to be an artist. His work was created in secret, most likely for personal fetishistic reasons, and was only found by his landlord some months after his death. In divorcing his illustrations from their private functional context and placing them within a public gallery arena, the function of these objects is changed. Something which may have had personal religious or devotional meaning becomes secularised, as an item for bourgeois cultural consumption.

In some cases it can be argued that the creator acted without any artistic intention, creating as part of a private personal belief system, rather than social reasons. For example, during his lifetime Henry Darger worked as a lavatory cleaner in Chicago hospital. He was never known as someone who wanted to be an artist. His work was created in secret, most likely for personal fetishistic reasons, and was only found by his landlord some months after his death. In divorcing his illustrations from their private functional context and placing them within a public gallery arena, the function of these objects is changed. Something which may have had personal religious or devotional meaning becomes secularised, as an item for bourgeois cultural consumption.